Christine Green, MD, is a Stanford-trained, board-certified family medicine physician with 30 years of experience treating patients with tick-borne illness. In this Q&A, she discusses common symptoms and the diagnostic process for Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases.

Q: I’m achy and tired all the time. Could I have Lyme disease?

The answer is yes. When a patient comes into my clinic for the first time, I take down their clinical history. If I suspect tick-borne disease, I ask if they’ve been exposed to ticks or tick habitats. Have they observed any rashes? The typical Lyme rash expands and is ring-like, usually not itchy or painful. If it’s under a person’s hairline, between the toes, or on the back of the body, it may not be noticed. At least 21% of Lyme patients, and probably more than 50%, never see a tick or a rash.

Early Lyme patients present with flu-like symptoms. Tick bites and resulting symptoms often occur in the summer, but in my California practice, Lyme season may overlap with the fall/winter flu season, confusing the diagnostic picture.

Next, I do a complete physical exam, with an emphasis on neurological deficits, such as loss of balance, tremors, facial asymmetry (Bell’s Palsy), and asymmetric reflexes. Then, I ask about the progression of their symptoms over time. In the first few months of Lyme disease, patients often experience malaise, fatigue, mild-to-severe headaches, nerve pain or tingling in the hands or feet, all in a relapsing-remitting course. In other words, the symptoms wax and wane.

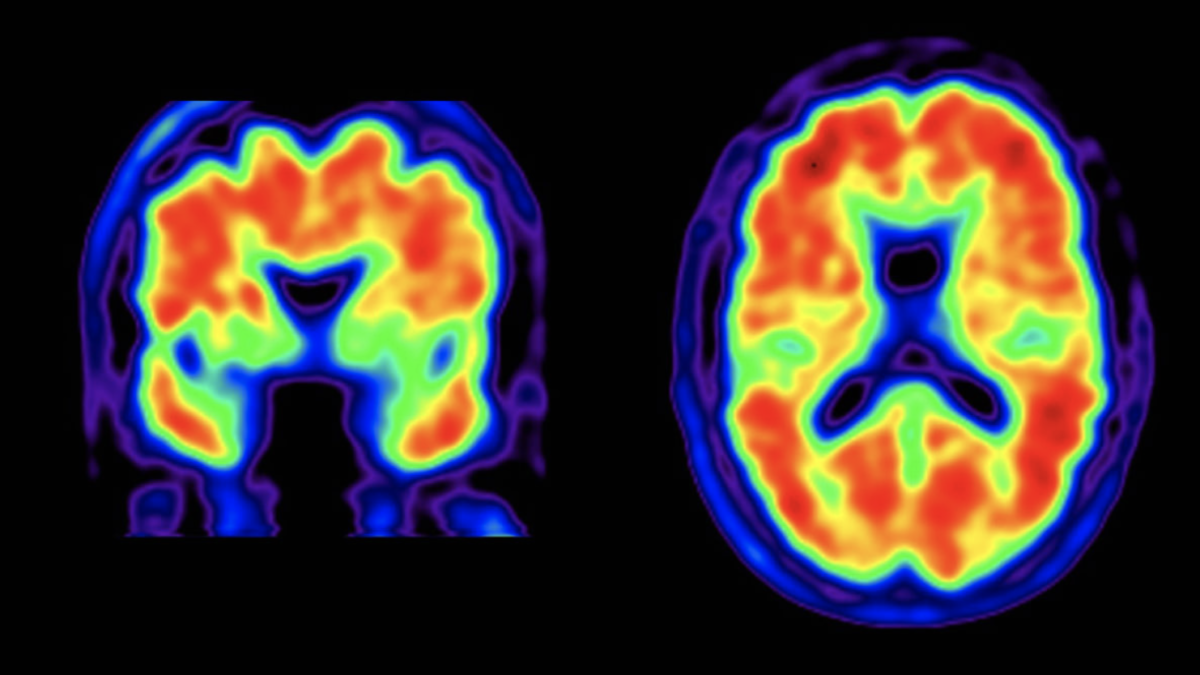

If Lyme is diagnosed four or more months after symptom onset, the picture of the disease is different and variable. The longer between infection and diagnosis, the higher likelihood that more bodily systems have been invaded. Late-stage patients tend to have peripheral nerve symptoms that come and go, and symptoms that migrate to joints, muscles and/or nerves. Most patients with late Lyme have encephalopathy, inflammation of the brain that reduces blood supply in some areas. It can manifest as sleep problems, memory issues, word-recall problems, or difficulty reading or carrying out executive functions, the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus, remember instructions, and juggle multiple activities. For instance, a person who organizes large events might find that they have trouble completing and sequencing tasks. Things that used to take minutes, take hours.

Patients can also experience cardiac symptoms, including irregular heartbeats, chest pain, or dizziness. These patients often come in misdiagnosed with old age, depression, anxiety, or hypochondriasis (preoccupation with an imagined illness). Another presentation of this disease is chronic pain. The pain can be widespread and migrate around the body. These patients often come in with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia or new onset migraine headache.

Q: What’s the best test for diagnosing Lyme disease?

First and foremost, Lyme disease, as with any disease, should be diagnosed based on a clinical history and physical exam, not by test results alone. It’s important to note that the complex, conservative two-tiered testing criteria for “CDC positive cases” was developed for disease-tracking only, and it shouldn’t be used by physicians as the sole criteria for diagnosis or denying treatment to patients. What’s more, not all Lyme tests are created equal. The major labs typically look for only one strain of Lyme bacteria, the B31 strain of Borrelia burgdorferi. I prefer using specialized labs that test for multiple Lyme strains. Three of the labs I use are MDL, Galaxy, and Igenex.

One tick can inject multiple species of disease-causing microbes in single blood meal, so, based on symptoms, I sometimes test for other tick-borne infections. If a patient has night sweats, shortness of breath, stabbing chest pains, or autonomic symptoms (dizziness, nausea, vertigo, flushing), I’ll test for babesia, a malaria-like red blood cell infection. For a pinprick rash on the extremities and/or severe illness, I’ll test for spotted fever. Bartonellosis can present in many ways, including neuropathy, or neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as panic attacks, rages, psychosis, and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Q: Once diagnosed, how should you treat Lyme disease?

Research over the last three decades suggests that Lyme bacteria have multiple ways of evading the human immune system and that treating acute Lyme with 21 days of antibiotics fails approximately a third of patients. For that reason, I treat in two phases. For early Lyme, I treat with four weeks of doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime antibiotics. I follow this up with four more weeks of drugs that prevent and eradicate “persister” forms of the bacteria. The persisters are drug-tolerant and can revert to an active infection once the antibiotics are stopped.

I treat late Lyme patients with severe degenerative neurologic or rheumatologic cases aggressively. As noted above, the very sick patients frequently have a mixture of tick-borne infections. For these patients, I choose a combination of oral or, when needed, intravenous antibiotics that target the pathogens known to be present.

Q: Can you cure chronic Lyme disease?

In my practice, I’ve helped many of my tick-borne disease patients return to full health. Every patient is unique, with different genetics, co-morbidities, and co-infections. To me, the important thing is to evaluate clinical response and not to cut off treatment at some arbitrary end point. I assess symptoms at the beginning of each visit, then treat until symptoms improve or resolve. For any patient who is ill for an extended time, after the illness is controlled, I initiate rehabilitation protocols to help the person feel normal again. A patient must become fit to fully recover from a protracted state of ill health.

——

For a checklist of common Lyme disease symptoms or to find an experienced tick-borne disease physician, visit the Lymedisease.org website.

To learn more about diagnosing and treating vector-borne diseases, watch Invisible International’s online, evidence-based physician medical education courses.